Cuba USA

“Some of this training was U.S. funded, although Colombia carried out many activities using its own resources, or that of other donors such as Canada,” the WOLA report states.“… Beyond official advertisements of the strategy and occasional, anecdotal press reports, little information is available about the extent and nature of Colombia’s training.

“While foreign aid law requires the United States to report to Congress in some detail about its own overseas training, these reports include no mention of U.S.-funded activities carried out by Colombian forces.”

The nature and sources of funding for Colombia’s exported military training may be opaque. But what is clear is that U.S. military training was provided to 4,486 members of Colombia’s security forces in fiscal 2013 at a cost to taxpayers of $32.9 million, according to the most recently available Foreign Assistance Act data. A good share of that training was in areas consistent with regional security operations, including courses in international counter-terrorism, advanced security cooperation, joint operations and international tactical communications.

The Colombian military and police training provided to Mexico’s security forces, Isacson says, is essentially a proxy arrangement, given the United States’ role in helping to fund and coordinate that training.

Colombians trained 10,000 Mexicans with the help of U.S. money,” he adds. “Our main concern is the lack of transparency and controls.”

- The "natural” Presence Of Us Armed Forces In Latin America

by Silvina M. Romanosource Alainet The discourse on freedom, democracy, diplomatic contacts and friendly relations with Latin America, so characteristic of the Obama administration in their eagerness to reinforce the "soft power" of his foreign policy,...

- One Year After The Disappearance Of The Students Of Ayotzinapa

by Santiago David Tavara source Alainet Advances at the pace of a turtle and a snail. The United States affirms that forced disappearances “have no place in a civilized society.” On the first anniversary of the disappearance of 43 students at...

- Mexico Accounts For Its Oil But Not Its Disappeared: Un

Source telesur U.N. human rights official says the Mexican government ignored U.N. recommendations three years ago, questioning why the country can account for its oil stocks, but not its disappeared. A top United Nations human rights work group...

- The Child Migration Crisis And The Legacy Of The Honduran Coup

By Dan Beeton Source: alainet.org In the years just before the June 28, 2009 coup d’état, Honduras was rarely in the U.S. news. In the five years since, Honduras has received much more coverage, but it’s all bad press. Most recently has...

- Violence Against Women In Mexico And Central America And The Impact Of U.s. Policy

“The war on drugs in Mexico, Honduras and Guatemala has become a war on women. Efforts to improve ‘security’ have only led to greater militarization, rampant corruption and abuse within police forces and erosion of rule of law. Ultimately, it has...

Cuba USA

US Military’s Training of Mexican Security Forces Continues As Human-Rights Abuses Mount In Mexico

by Bill Conroy

source narcopshere

DoD Officials Claim Training is Part of the Solution, Not the Problem

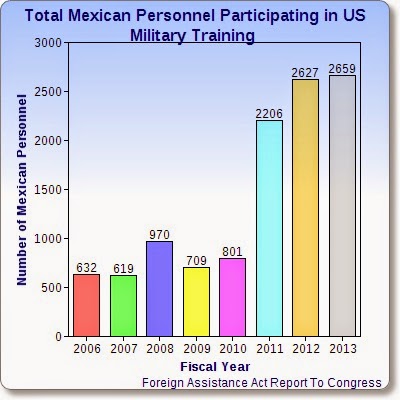

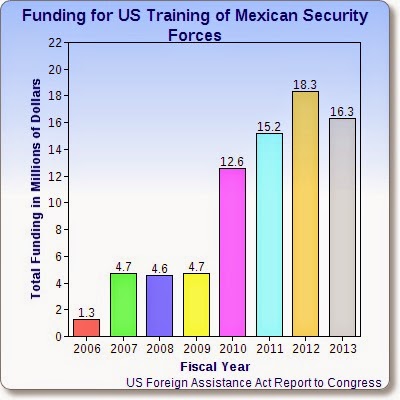

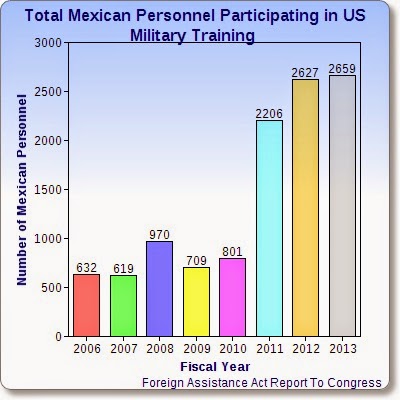

The U.S. government has spent more than $62 million since fiscal year 2010 providing highly specialized training to Mexican security forces, including some $16.3 million in fiscal 2013, as part of an effort to help Mexico better prosecute its war on drugs, records made public under the U.S. Foreign Assistance Act show.

The spending has continued even as Mexico’s military and police forces continue to face accusations of pervasive human-rights abuses committed against Mexican citizens, leading some experts to question whether the U.S.-funded training is resulting in some deadly unintended consequences.

The news of the disappearance in late September of 43 students who attended a rural teachers college in Ayotzinapa, located in the southern Mexican state of Guerrero, has sparked massive protests in Mexico. The students were allegedly turned over to a criminal gang after being abducted by Mexican police and they remain missing. The police fired on the three buses transporting the students along a stretch of road near Iguala, about 130 kilometers north of Ayotiznapa, and the abduction was carried out near a Mexican military base, according to Human Rights Watch.

The Ayotzinapa incident was preceded by a lesser-known attack this past June during which Mexican soldiers killed 22 people inside a warehouse in Tlatlaya, 238 kilometers southwest of Mexico City. At least 12 of those homicides were deemed extrajudicial executions, according to Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission [CNDH in its Spanish initials].

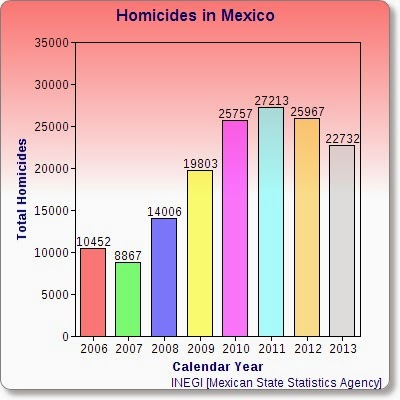

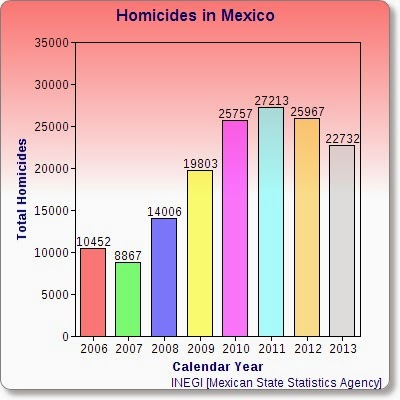

Last year, the Mexican government conceded that at least 26,000 people had gone missing, or been disappeared, in Mexico since 2006 — the year the war on the “cartels” in that nation was launched. Over that same period, INEGI (the Mexican State Statistics Agency) reports, there were some 155,000 homicides in Mexico, most with a nexus to the drug war.

The U.S. Department of Defense insists that the relationship it has with Mexican security forces is based on “trust and confidence and mutual respect” and is critical to helping to reduce the violence sparked by criminal organizations in Mexico.

The U.S. training, funded through the DoD and to a lesser extent the U.S. Department of State, encompasses a wide range of military strategy and tactics and is carried out at locations in the United States and inside Mexico. Among the course topics on the menu are asymmetrical conflict, counter intelligence, international counterterrorism, psychological operations, counter-drug operations and urban operations. The training is being provided to a broad spectrum of Mexican security forces, including the Army, Navy and the federal police, according to data provided to Congress under the requirements of the Foreign Assistance Act and is current through fiscal year 2013.

Adam Isacson, senior associate for regional security policy with the Washington Office on Latin America, a nongovernmental organization promoting human rights and democracy in Latin America, says there is a lack of reliable public data on data provided to Congress under the requirements of the Foreign Assistance Act and is current through fiscal year 2013.

Adam Isacson, senior associate for regional security policy with the Washington Office on Latin America, a nongovernmental organization promoting human rights and democracy in Latin America, says there is a lack of reliable public data on the fate of Mexican security forces after they receive U.S. military training.

“While foreign aid law requires the United States to report to Congress in some detail about its own overseas training, these reports include no mention of U.S.-funded activities carried out by Colombian forces.”

The nature and sources of funding for Colombia’s exported military training may be opaque. But what is clear is that U.S. military training was provided to 4,486 members of Colombia’s security forces in fiscal 2013 at a cost to taxpayers of $32.9 million, according to the most recently available Foreign Assistance Act data. A good share of that training was in areas consistent with regional security operations, including courses in international counter-terrorism, advanced security cooperation, joint operations and international tactical communications.

The Colombian military and police training provided to Mexico’s security forces, Isacson says, is essentially a proxy arrangement, given the United States’ role in helping to fund and coordinate that training.

“Colombians trained 10,000 Mexicans with the help of U.S. money,” he adds. “Our main concern is the lack of transparency and controls.”

“What happens to these trainees a year or two down the road after they are placed in areas dominated by organized crime?” Isacson asks. “We simply don’t have good after-training tacking of these people, and the amount they are paid can’t compete with the drug money. Plus, the risk of getting caught is small. The biggest risk for them isn’t jail, but rather running afoul of the drug organizations.”

From fiscal 2010 through 2013, U.S. military training was provided to some 8,300 members of Mexico’s security forces, according to Foreign Assistance Act data. That training is overseen by U.S Northern Command (Northcom), a Department of Defense branch created in 2002 that is responsible for U.S. homeland defense as well as security cooperation efforts with the Bahamas, Canada and Mexico.

Northcom officials contend that all Mexican security forces receiving U.S. training are well vetted and that data is maintained on all participants. The training is designed to compliment Mexico’s existing efforts to maintain security and stability in the country.

“We do not believe that U.S. military training enables corruption and human rights violations,” Air Force Master Sgt. Chuck Marsh, spokesman for Northcom, says. “On the contrary, U.S. military members who provide training serve as positive role models, displaying professional values for foreign security forces to emulate. They conduct this training in strict accordance with the Leahy Law, which requires us to ensure individuals and units with whom we work are not involved in human rights violations.”

Still, in a country where fewer than 13 percent of crimes are even reported, according to a recent Congressional Research Service report, and where tens of thousands of murders and cases of disappeared individuals remain unresolved, it’s difficult to accept with certainty that the data maintained on U.S.-trained Mexican security forces is of much use in monitoring corruption. If human-rights abuses are not reported, much less investigated, then there’s nothing to track.

Mexico’s Military Prosecutor’s Office between 2007 and mid-2013 opened 5,600 cases into alleged human-rights abuses by soldiers, Human Rights Watch reports. Yet, as of October 2012, only 38 cases had resulted in convictions and sentences from military judges.

The nature and sources of funding for Colombia’s exported military training may be opaque. But what is clear is that U.S. military training was provided to 4,486 members of Colombia’s security forces in fiscal 2013 at a cost to taxpayers of $32.9 million, according to the most recently available Foreign Assistance Act data. A good share of that training was in areas consistent with regional security operations, including courses in international counter-terrorism, advanced security cooperation, joint operations and international tactical communications.

The Colombian military and police training provided to Mexico’s security forces, Isacson says, is essentially a proxy arrangement, given the United States’ role in helping to fund and coordinate that training.

“Colombians trained 10,000 Mexicans with the help of U.S. money,” he adds. “Our main concern is the lack of transparency and controls.”

“What happens to these trainees a year or two down the road after they are placed in areas dominated by organized crime?” Isacson asks. “We simply don’t have good after-training tacking of these people, and the amount they are paid can’t compete with the drug money. Plus, the risk of getting caught is small. The biggest risk for them isn’t jail, but rather running afoul of the drug organizations.”

From fiscal 2010 through 2013, U.S. military training was provided to some 8,300 members of Mexico’s security forces, according to Foreign Assistance Act data. That training is overseen by U.S Northern Command (Northcom), a Department of Defense branch created in 2002 that is responsible for U.S. homeland defense as well as security cooperation efforts with the Bahamas, Canada and Mexico.

Northcom officials contend that all Mexican security forces receiving U.S. training are well vetted and that data is maintained on all participants. The training is designed to compliment Mexico’s existing efforts to maintain security and stability in the country.

“We do not believe that U.S. military training enables corruption and human rights violations,” Air Force Master Sgt. Chuck Marsh, spokesman for Northcom, says. “On the contrary, U.S. military members who provide training serve as positive role models, displaying professional values for foreign security forces to emulate. They conduct this training in strict accordance with the Leahy Law, which requires us to ensure individuals and units with whom we work are not involved in human rights violations.”

Still, in a country where fewer than 13 percent of crimes are even reported, according to a recent Congressional Research Service report, and where tens of thousands of murders and cases of disappeared individuals remain unresolved, it’s difficult to accept with certainty that the data maintained on U.S.-trained Mexican security forces is of much use in monitoring corruption. If human-rights abuses are not reported, much less investigated, then there’s nothing to track.

Mexico’s Military Prosecutor’s Office between 2007 and mid-2013 opened 5,600 cases into alleged human-rights abuses by soldiers, Human Rights Watch reports. Yet, as of October 2012, only 38 cases had resulted in convictions and sentences from military judges.

Mexico’s CNDH reported last year that Mexican security forces were suspected of playing a role in at least 2,443 cases in which people were disappeared. Human Rights Watch, in a study released last year, said it “found evidence that members of all branches of the [Mexican] security forces carried out enforced disappearances.”

“Virtually none of the victims have been found or those responsible brought to justice,”Human Rights Watch reports.

WOLA’s Isacson says there is no evidence at this point directly linking human-rights abuses by Mexican security-forces to U.S. military training, but adds that “the risk is huge.”

“Congress a few years ago required DoD to keep more records on trainees, but that information is classified,” he adds.

What’s lacking is quantifiable public data that can be used to assess the effectiveness of U.S. training of Mexico’s security forces or the human-rights track record of trainees after the training is finished. “That evaluation has to now be based mostly on blind faith,” Isacson says.

And in yet another wrinkle to the military-training issue, Isacson points out that the U.S. military is helping to fund Colombia’s export of military training to other nations as part of its security coordination with the South American nation. Colombia provided military and police training to more than 10,310 members of Mexico’s security forces between 2009 and 2013, according to a recent WOLA report that uses figures provided by the Colombian National Police.

“Virtually none of the victims have been found or those responsible brought to justice,”Human Rights Watch reports.

WOLA’s Isacson says there is no evidence at this point directly linking human-rights abuses by Mexican security-forces to U.S. military training, but adds that “the risk is huge.”

“Congress a few years ago required DoD to keep more records on trainees, but that information is classified,” he adds.

What’s lacking is quantifiable public data that can be used to assess the effectiveness of U.S. training of Mexico’s security forces or the human-rights track record of trainees after the training is finished. “That evaluation has to now be based mostly on blind faith,” Isacson says.

And in yet another wrinkle to the military-training issue, Isacson points out that the U.S. military is helping to fund Colombia’s export of military training to other nations as part of its security coordination with the South American nation. Colombia provided military and police training to more than 10,310 members of Mexico’s security forces between 2009 and 2013, according to a recent WOLA report that uses figures provided by the Colombian National Police.

“Some of this training was U.S. funded, although Colombia carried out many activities using its own resources, or that of other donors such as Canada,” the WOLA report states.“… Beyond official advertisements of the strategy and occasional, anecdotal press reports, little information is available about the extent and nature of Colombia’s training.

“While foreign aid law requires the United States to report to Congress in some detail about its own overseas training, these reports include no mention of U.S.-funded activities carried out by Colombian forces.”

The nature and sources of funding for Colombia’s exported military training may be opaque. But what is clear is that U.S. military training was provided to 4,486 members of Colombia’s security forces in fiscal 2013 at a cost to taxpayers of $32.9 million, according to the most recently available Foreign Assistance Act data. A good share of that training was in areas consistent with regional security operations, including courses in international counter-terrorism, advanced security cooperation, joint operations and international tactical communications.

The Colombian military and police training provided to Mexico’s security forces, Isacson says, is essentially a proxy arrangement, given the United States’ role in helping to fund and coordinate that training.

Colombians trained 10,000 Mexicans with the help of U.S. money,” he adds. “Our main concern is the lack of transparency and controls.”

- The "natural” Presence Of Us Armed Forces In Latin America

by Silvina M. Romanosource Alainet The discourse on freedom, democracy, diplomatic contacts and friendly relations with Latin America, so characteristic of the Obama administration in their eagerness to reinforce the "soft power" of his foreign policy,...

- One Year After The Disappearance Of The Students Of Ayotzinapa

by Santiago David Tavara source Alainet Advances at the pace of a turtle and a snail. The United States affirms that forced disappearances “have no place in a civilized society.” On the first anniversary of the disappearance of 43 students at...

- Mexico Accounts For Its Oil But Not Its Disappeared: Un

Source telesur U.N. human rights official says the Mexican government ignored U.N. recommendations three years ago, questioning why the country can account for its oil stocks, but not its disappeared. A top United Nations human rights work group...

- The Child Migration Crisis And The Legacy Of The Honduran Coup

By Dan Beeton Source: alainet.org In the years just before the June 28, 2009 coup d’état, Honduras was rarely in the U.S. news. In the five years since, Honduras has received much more coverage, but it’s all bad press. Most recently has...

- Violence Against Women In Mexico And Central America And The Impact Of U.s. Policy

“The war on drugs in Mexico, Honduras and Guatemala has become a war on women. Efforts to improve ‘security’ have only led to greater militarization, rampant corruption and abuse within police forces and erosion of rule of law. Ultimately, it has...